Our People are in the Mines: Prioritizing Education and Environment in Mining Communities

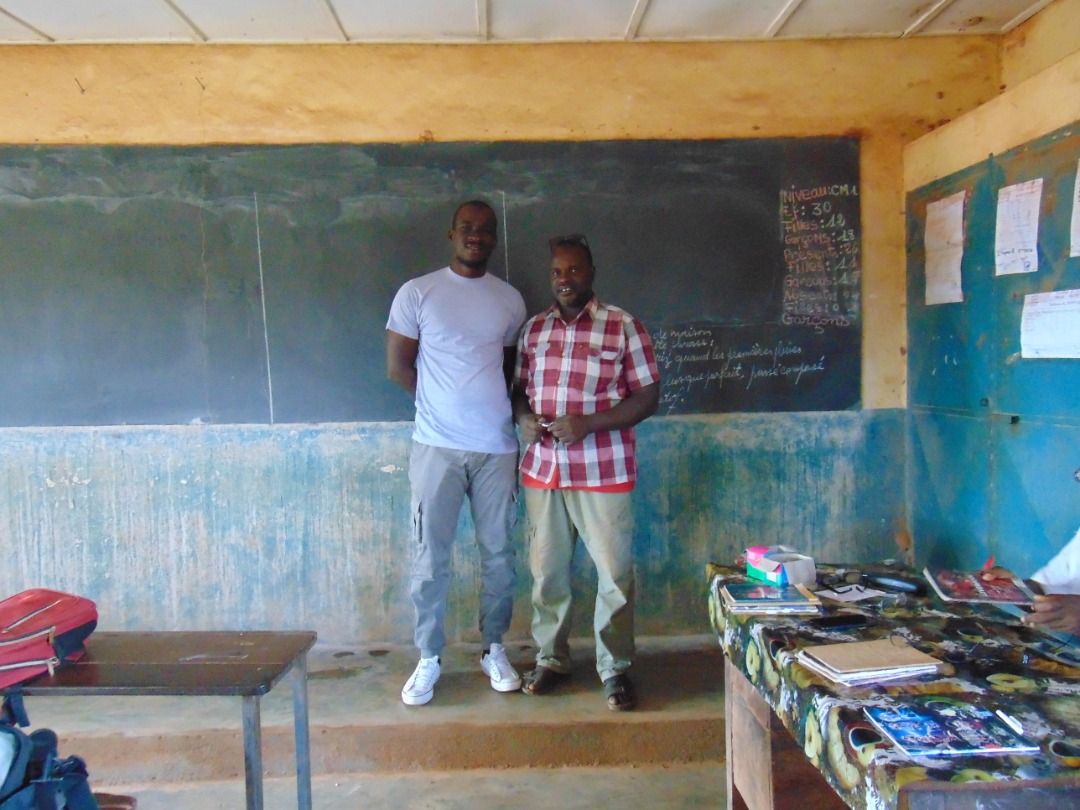

Ibrahima Kalil Gueye is a 2018 Fellowship Alumnus and the winner of the 2020 Leadership Impact Award. A good governance advocate, Ibrahima promotes grassroots citizen education and policy reform through Open and Transparent Guinea. In this piece, Ibrahima reflects on his travels to mining communities in Guinea and calls on young African leaders to protect those most negatively impacted by extractive industries: school-aged youth and communities in poverty. Learn more about Ibrahima and his work.

In many African countries, the mining industry is seen as an essential sector of the economy. But what is the true measure of wealth when the communities where the extractions occur live in precarious conditions, and the industry operates at the cost of their education and welfare?

In Guinea, difficult living conditions in mining areas often push their residents to take their children out of school and practice artisanal mining to meet basic needs. For several years, there has been a considerable drop in the level of education of children in mining areas. This is a lose-lose situation, where the communities are negatively impacted, and the youth lose the necessary training to flourish.

As young African leaders, one of our top priorities should be helping these young people to access better education as an alternative to mining practices. We need more advocacy to enforce international standards on mining, child labor, environmental protection, as well as children’s right to education. This is not isolated to Guinea; communities throughout Africa and other parts of the world have faced many consequences due to the mining industry. I hope that my reflections of what is happening in my own country will inspire you to learn more about what may be happening in your own.

Impact on Education

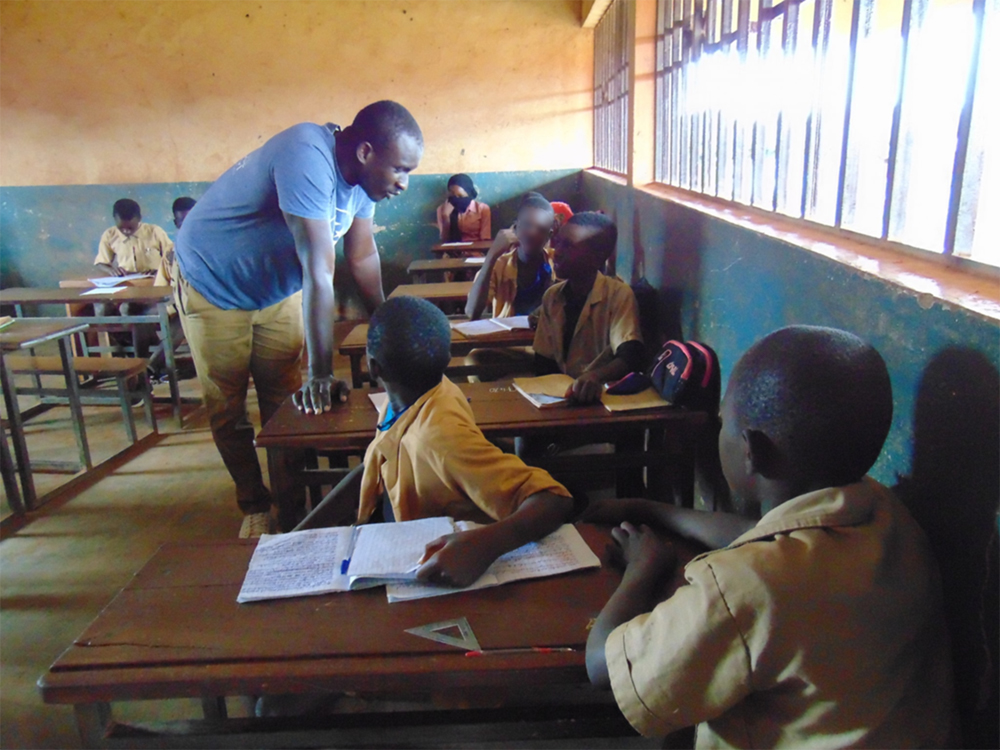

I spent the months of July and August 2020 in northern Guinea in the mining region of Bouré, primarily in Siguiri. The purpose of this trip was to identify and assess the problems that citizens are facing, including the impact on children’s education and the community, and to help them create collaborative solutions to tackle these challenges.

There are many factors that complicate life for children in mining communities. Oftentimes, parents who work in the mining industry are forced to either leave their young children at home unattended or to take them to the mines with them all day. Authorities struggle to take appropriate measures against child labor violations.

Additionally, the level of education of children in these mining areas has trended downward in recent years. The education system in Siguiri is chaotic, at best. The few children who are able to go to school often do not receive a quality basic education due to the dire shortage of teaching staff. In some cases, the communities themselves, instead of the government, pay teachers to provide the minimum instruction in schools. In the village of Fadako, the community built its own school with six classrooms. However, as the administration and teaching are managed by only one person, they can only hold four classes. This continues despite efforts at the level of the Sub-Prefecture of Education to assign a few tenured teachers to support the school.

According to the Guinean NGO Action Mine, between 2017 and 2019, artisanal gold mining was linked to more than 3,600 children dropping out of school. By the time the children reach adolescence, almost all of them drop out of school and end up working in the mines. The gap between enrollment and completion rates in Siguiri schools is alarming: out of the 97% of children enrolled in primary schools, only 33% actually complete their primary education. Even worse, only 6.3% finish middle school and 17.9% complete high school. The school dropout rates in some localities like Norassoba and Tombôkhô have often been as high as 90 to 97%.

Broader Community and Environmental Impacts

Even among educated people in these communities, residents are un- or underemployed and living in poor conditions. Mining is often seen as the pathway to affording a basic livelihood and other goods such as motorcycles, cars, and houses.

Though artisanal mining is the main income-generating activity in these communities, and in many like it, people still struggle to reduce the level of poverty in these areas. These artisanal miners use their own means, from hands, picks, shovels, and calabashes to dig in expansive pits – all in pursuit of a few grams of gold.

This is, of course, is not without consequence. Environmentally destructive mining practices, scarce rains, and high costs of living in mining zones negatively affect the few farmers who live in the region. The growing impact of mining equipment along the streams and backwaters of the region have caused water sources to dry up and farmers to lose their livelihood.

How Can We Help?

In my role as a good governance advocate, I pledge to devote my future travels to this area to raising awareness about promoting education, preventing school dropouts, and regulating artisanal mining and environmental protection.

Won’t you join me in this fight? As young African leaders, one of our major priorities should be helping these young people to access better education as an alternative to mining practices that do not actually help them. We need more advocacy in our various countries to enforce international standards on mining, child labor, environmental protection, as well as children’s right to education. Let us also take this issue higher and demand lasting international actions for our brothers and sisters who continue to be exposed to harmful mining practices and inequality.

Education will always do what mines can never do! Our people’s lives are at stake – let us act for them.

The Mandela Washington Fellowship is a program of the U.S. Department of State with funding provided by the U.S. Government and administered by IREX. The views expressed in this piece are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Government.

See More Photos from Ibrahima’s Trip

Next Story

Rebecca Ebenezer-Abiola

2017 Fellowship Alumna, Nigeria